Curators on hosting the first ASMR exhibition in Asia

May 12, 2025

As Hong Kong becomes the first Asian city to host the world’s first immersive exhibition dedicated to ASMR, curator James Taylor-Foster and local co-curator Daisy Chu talk to Jaz Kong about feelings, vulnerability and why we need more spaces to play like kids again

Autonomous sensory meridian response, or ASMR, is defined as “a pleasant tingling sensation that originates on the back of the scalp and often spreads to the neck and upper spine, that occurs in some people in response to a stimulus (such as a particular kind of sound or movement), and that tends to have a calming effect”. Since the term was first popularised in 2011, people in Hong Kong have mostly experienced the curious sensation while watching videos on YouTube or social media. Not anymore – as of last month, Kai Tak’s Airside is home to the world’s first ASMR exhibition.

WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD: The World of ASMR bridges the on- and offline experience to bring a private – and, in some sense, taboo – enjoyment to a public stage. On view until July 13 at GATE33 Gallery, the immersive multi-sensory exhibition is co-presented by ArkDes, the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design, and the Design Museum, London. James Taylor- Foster, ArkDes’s curator of contemporary architecture and design, is the lead curator with the new Hong Kong section co-curated by Airside’s Daisy Chu.

The exhibition’s arrival in Hong Kong can be traced back to around 2022, when Chu visited an earlier edition of WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD: The World of ASMR in London. Describing herself as an impatient person, she was surprised to spend almost three hours at the exhibition. “I loved how immersive it was – it’s different from a digital art or hologram projection immersive experience – and how physical it was. I really wanted to bring it to Airside as it would be a perfect space for it, and a good chance for visitors to explore the boundary of art and culture. We also wanted to create a bridge between local artists, international institutions and our audience, and this exhibition is truly a pioneering one for Airside.”

WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD: The World of ASMR’s Hong Kong version consists of five parts, beginning with “The Origins of ASMR”. This provides a bit of background, from the first online discussions of the sensation around 2007 to the term Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response being coined by Jennifer Allen in 2010 and its first Wikipedia entry in 2011 – which, according to Allen, was soon taken down because “it didn’t meet the standards of the Wikipedia editors and was quickly voted against for removal”.

“ASMR was truly only discovered because of the Internet,” says Taylor-Foster of the debates over whether it’s an example of pseudoscience. “Whether ASMR medically exists or not, that’s up for discussion. People are doing research into that right now. But this is what I love about cultures of creativity – they can come out of nowhere.”

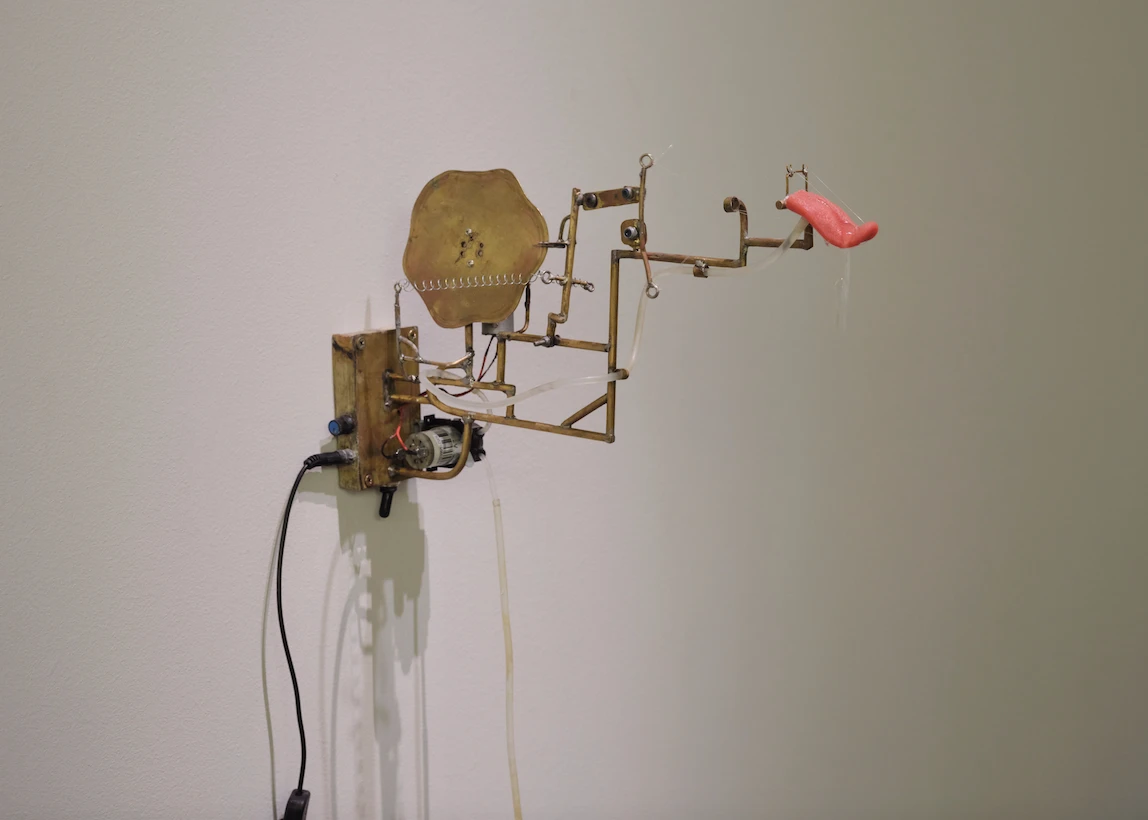

What’s different about the Hong Kong show versus the previous ones in Stockholm and London is the addition of “Hong Kong-Themed Artworks Explore a Local Perspective”, which Chu curated to feature newly commissioned works by locally-based artists AK Kan and Kin Lam – a field-recording artist and sound design artist, respectively – that showcase the city’s unique auditory identity and offer a regional perspective on this global phenomenon. One of the changes Kan and Lam made to the ASMR creation station is the addition of everyday Hong Kong objects, including flip-flops (like the ones used in the folk sorcery da siu yan, or villain hitting), bamboo dim sum steamers, calligraphy brushes and more.

Another work, which Taylor-Foster describes as an uncanny experience, is I Can Sleep Standing, Let Alone Sitting, which recreates scenarios in which Hongkongers often fall asleep on public transport and depicts situations of unintentional ASMR triggered by everyday scenes and sounds, allowing audiences to immerse themselves in the meditative soundscapes of the local MTR, bus and minibus. “I think the Hong Kong section gives visitors some kind of local intimacy while they’re diving into other kinds of ASMR experiences here,” says Chu.

“I think ASMR is also so much based on the ordinary objects of everyday life. And that’s what I really like about what [Kan and Lam] are doing, actually,” adds Taylor- Foster. “They’re elevating this experience for a lot of people in Hong Kong who maybe don’t quite think of ASMR as that sort of experience. But you first need to decontextualise it, and then you recontextualise it, and then you start to see it in a different way. And really, that’s ultimately what this exhibition is about. It’s about a few different layers of things, but one of the best things I would hope for is that when visitors leave, maybe they can hear something in a different way. Maybe they hear a bird rather than a drill.”

One of the common features of the Stockholm, London and Hong Kong shows is the ASMR Arena, featuring over a kilometre of “sausage pillow” allowing visitors to take off their shoes and sit or even lie down to enjoy the 13 audiovisual works representing different forms of ASMR. Taylor-Foster calls this room “a big hug”, and he goes on to explain that “exhibitions are social spaces, right? So like most people think, you go to an exhibition to see things on a wall. But I say, no, we come to exhibitions to see other people and then we look at things.

“So we created this kind of acoustically-tuned environment where you can whisper and still sort of hear each other. But then it’s also just essentially like a massive sofa where you can hang out, and we’ve had people fall asleep. It’s the only exhibition I’ve ever had where I say people falling asleep is a compliment.” Chu also shares an experience on the first day of the opening, saying, “I’ve never led a tour where the kids don’t scream or run around. When they entered this acoustic arena, they went super calm.”

That also explains why Dagnija Smilga and her architecture studio Ēter were awarded the Dezeen Exhibition Design of the Year award in 2022. “Every exhibition we make, architecture is a very important part of it,” explains Taylor-Foster, “because that’s how you construct the context. When it comes to this particular case, the pillow is not the most radical thing in the world. It feels a little like a brain. When you first walk in here, even though it’s weird, very quickly it feels familiar, because we all understand what softness is. But then you don’t expect to experience it out in the city necessarily. So we’re just trying to recreate a space where you actually might feel safe, because this is an exhibition about a feeling, right? And you need a little bit of vulnerability in order to feel.”

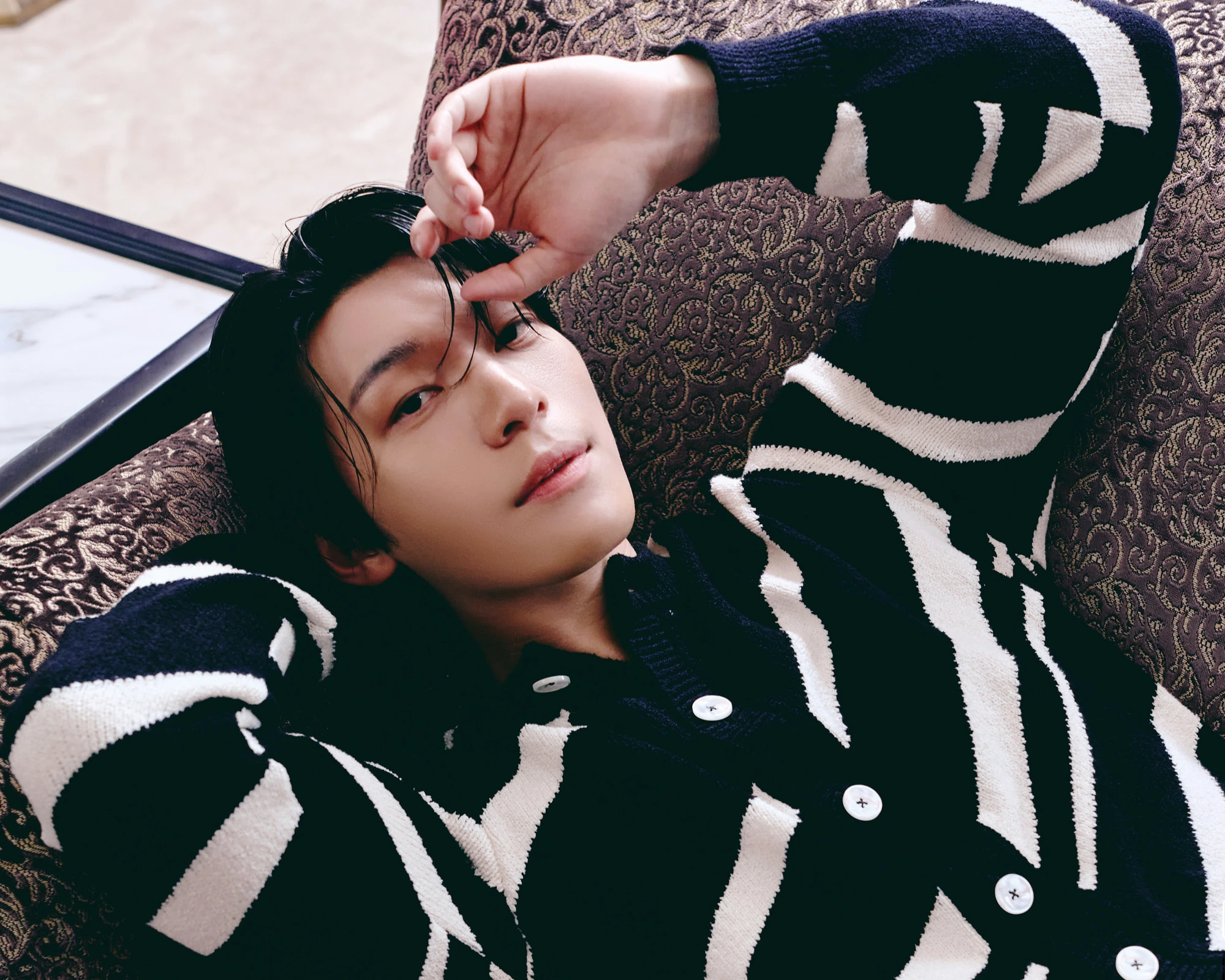

Also see: #interview: Lauren Tsai, the girl who blends the worlds of Disney, Ghibli and Tim Burton in her art

Another layer of vulnerability is reflected in the setting of the exhibition. “What I’m getting at when I talk about this question of vulnerability is that ASMR is mostly consumed in private, in bed, at night, under the blanket, in the darkness. And so this was an experiment to try to think about what a space of public shared feeling might look like. And you can have any response. You can have a total disgust for ASMR, or you can be

in a state of complete euphoria and relaxation. But it’s really important that we construct spaces of respect in public,” says Taylor-Foster. “In the exhibition booklet, we ask people to acknowledge their own vulnerability, to respect the vulnerability of others and to be considerate. And you know, somebody might be feeling something completely different to you and we should respect that. I do think, generally in societies, we need to embrace feeling more. We ignore it so much in so many aspects of culture. When you go to a big museum everyone has the same expression on their face. But actually the whole point of art and culture is to evoke strong feelings. So I try to nurture spaces that allow for that.

“It touches on something that I think is really important – when you’re a kid, you know how to play. Just automatically, at some point, you stop playing. Everything becomes really serious and you don’t want to create. And I think that actually what culture should be doing more and more is constructing spaces for what I call serious play or adult play, where it’s okay to have that curiosity and to want to touch that thing and want to giggle a bit and also to take it seriously. It’s actually a fundamental part of what it means to be human.”

Taylor-Foster recalls the Stockholm and London shows bookending COVID-19 as he views the Hong Kong exhibition. “We’re now seeing, after the effects of the pandemic, that a new relationship to technology has developed. And it’s predominantly among young people, but there’s a big trend now towards analog experiences. This exhibition has stood the test of time because this is what it was doing five years ago and is still doing now. So in a way, it’s morphing with different contemporary trends surrounding ASMR and our relationship to what I call digital intimacy.

“I’m very interested in the emerging and peripheral forms of design and creativity that I think can tell us something about the way in which we’re living today. Back in 2019, when nobody knew what ASMR was, and it was also kind of taboo, I was already really sure about it. I was sure that there was something important that ASMR as a culture and a community in a creative field could teach us about loneliness, new structures of collective intimacy, and the relationship between technology and creativity.”

If design is to tackle society’s problems, what exactly is Taylor-Foster trying to solve? “ASMR is interesting because it’s trying to recreate touch. It’s driven through screens, because for better or for worse, it’s the culture that we exist within, and it’s a visually dominant culture. However, ASMR is about movement and sound and the recreation of touch. Even though it seems abstract, like a background thing, sound is actually physical. For example, when you lean your head against the glass on the bus, it’s physical, because there are physical sound waves.”

On a deeper level, especially after the pandemic, Taylor-Foster finds it important to connect with other people and, even more importantly, with ourselves. “What the exhibition is trying to do is stop us talking about visual relationships and audio relationships as separate things when they’re indeed all connected. Just outside here, we have a sign that says, ‘The design that mediates between mind and body.’ It’s kind of a controversial thought, because the separation of brain and body has been a thing for hundreds of years. Like in medical science, predominantly in the West, when you hear about a neurological disease or depression, for example, it’s as much affected by your gut and what you eat. It’s not just in your brain.

“At least from a design perspective, we’re trying to dismantle that. ASMR is interesting, because it’s touching your brain and your body – it’s touching you psychologically and physiologically at the same time. And I think it’s nice to come into a space and just think about something that you might not have thought about. For example, what’s my relationship to anxiety or to screens in general?”

The feeling of ASMR has been around for a long time, long before it was defined as ASMR. However, there must be a reason for the boom in demand, especially in our anxiety-ridden digital age. Is it the ultimate solution to our mental problems? Absolutely not, but it does actually feel good to admit that this weird sensation feels good.

Also see: #interview: Architect Martin Brudnizki on designing Hong Kong's Deep Water Pavilia and luxury living