Director Daihachi Yoshida on turning Teki Cometh into a movie

May 15, 2025

In town to collect his trophy at the Asian Film Awards, director Daihachi Yoshida talks to Mathew Scott about adapting a novel for film and being a latecomer to movies

Let’s put it all down to timing. As Japanese director Daihachi Yoshida readily admits, the opportunity to reread Yasutaka Tsutsui’s novel Teki Cometh (1998) only came around because of forces beyond his control.

Pandemic-enforced lockdowns had forced him inside for extended periods where he couldn’t work and he turned to his library for entertainment. Yoshida had read Teki Cometh before – probably two decades ago – but the second time around the resonance was unmistakable.

That’s mainly because the novel’s tale centres around an ageing man who pretty much spends all his time inside his home, where he is increasingly faced with the memories that both haunt and support him.

“The second time around was a period when everybody was forced to spend a

lot of time alone with their thoughts,” the filmmaker explains.

We’re chatting with Yoshida on the afternoon before he picks up the Best Director award for his efforts in turning Teki Cometh into a movie. The film previously scooped the same award, plus Best Film and Best Actor, at the Tokyo International Film Festival, which tells you all you need to know about how good it is.

Yoshida builds here on his reputation as one of the most distinctive voices in Japanese cinema with a languid look at ageing, and how people cope. It’s a film that takes surprisingly dark and even erotic twists, with a masterful central performance from the veteran actor Kyôzô Nagatsuka, one that leaves you questioning what to actually believe.

That’s the point, too. Teki Cometh is also a film that questions memories and how closely they actually stick to the truth of what occurred, or how often we protect ourselves by simply changing the narrative to suit.

It’s screening at April’s Hong Kong International Film Festival – if you’re lucky (and quick) enough to secure tickets.

Yoshida was a latecomer to movies, shifting his focus from making commercials when in his 40s, but he’s since found regular critical acclaim by looking to literature as his source material, beginning with his breakthrough Funuke: Show Some Love, You Losers! (2007), which screened at Cannes, taken from a novel that digs deep into one family’s multiple dysfunctions, and on through the likes of the Japanese Film Academy Best Director award-winning The Kirishima Thing (2013), which looks at the high dramas of high school.

Today, he’s relaxed and warm and generous with his opinions as we try to delve into a film that (ahem) for people of a certain age (and others, promise!) will certainly strike distinctive chords. “There are issues here that we all have to face,” says the director, “no matter whether we want to or not.”

You have said you first read the novel as a much younger man. Could that younger man have made this movie?

I don’t think so. What has changed is my body’s condition as well as my outlook on life. As one ages, the concept of getting older becomes a more serious issue. When

I read it this time, I actually felt a little relieved in a way, because it helped me realise you can’t avoid getting older or your decline. After reading the novel again, I realised that if I face this with determination, the feeling of fear will slightly diminish. The protagonist also wants to become like that, but the protagonist is naturally more of an individual than I am now, so he ends up unable to stop himself from falling apart. I want to be a little more flexible than the protagonist, but I don’t know how I will actually feel when I reach his age.

You read it again during the pandemic, too, so did those themes of being confined resonate?

Perhaps people all over the world are now living similar lives to the protagonist. When I read it for the first time, I hadn’t even started making movies yet, so I never thought about making it into a movie. But now that I have started making movies to some extent – and I’m in my late 60s – it was fateful to read the novel again. At that time, when everyone couldn’t leave their homes, they couldn’t change their lives, it just felt like fate had led me back to the novel. I think it’s all about timing. I started directing films after the age of 40, so the protagonists were often younger than me or of the same generation, but for the first time in this case, I portrayed a protagonist older than myself.

Why did it take so long for you to turn to movies?

In my younger days, I was involved in various businesses such as making commercials and music videos, and I didn’t feel my career was lacking anything. I liked watching movies, but I didn’t have a strong desire to make movies. However, when I read the original novel of my first film [2007’s Funuke: Show Some Love, You Losers!], a strange sensation occurred where the movie suddenly appear ed completed in my mind. That was the trigger.

Also see: #review: Is Mickey 17 starring Robert Pattinson worth a watch?

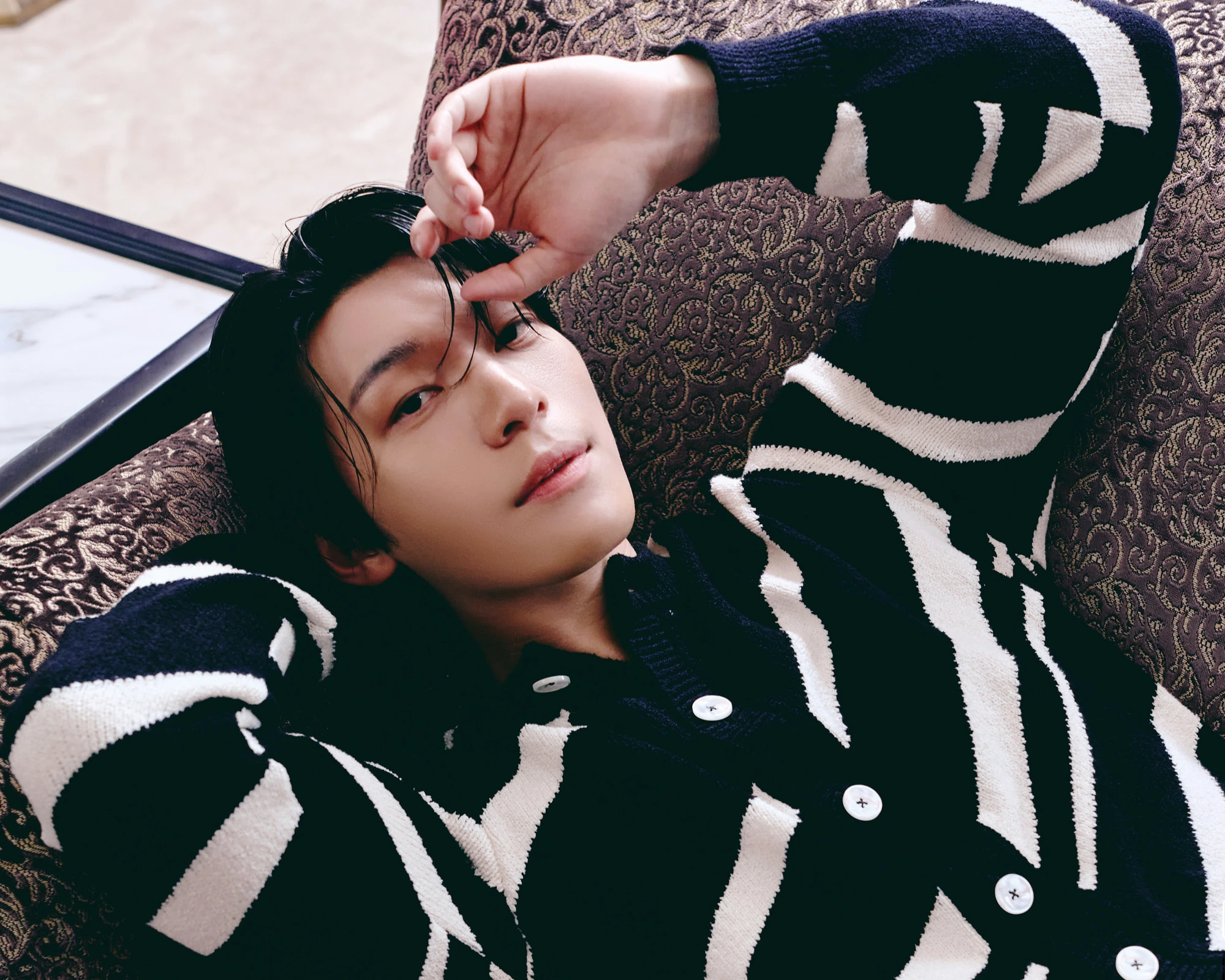

Kyôzô Nagatsuka is brilliant in the lead. How did he connect with the character?

The protagonist really carries the story, and that’s what Nagatsuka-san does. Before the shoot, we read the script together and what was quite significant was that Nagatsuka- san also writes books, such as essays about his own life or his work as an actor, and that was really suggestive for me, giving me various inspirations. During filming, Nagatsuka-san and Gisuke became equals, so I didn’t call Nagatsuka-san by name on set. Instead, I referred to both of them as Gisuke-san. When I stood in front of the camera, I felt like the protagonist Gisuke- san that I had imagined was really there. Actually, Gisuke taught French literature and Nagatsuka-san actually studied in France for about eight years when he was young, graduated from a university in France, and shot his first movie in France. So there was a deep connection already.

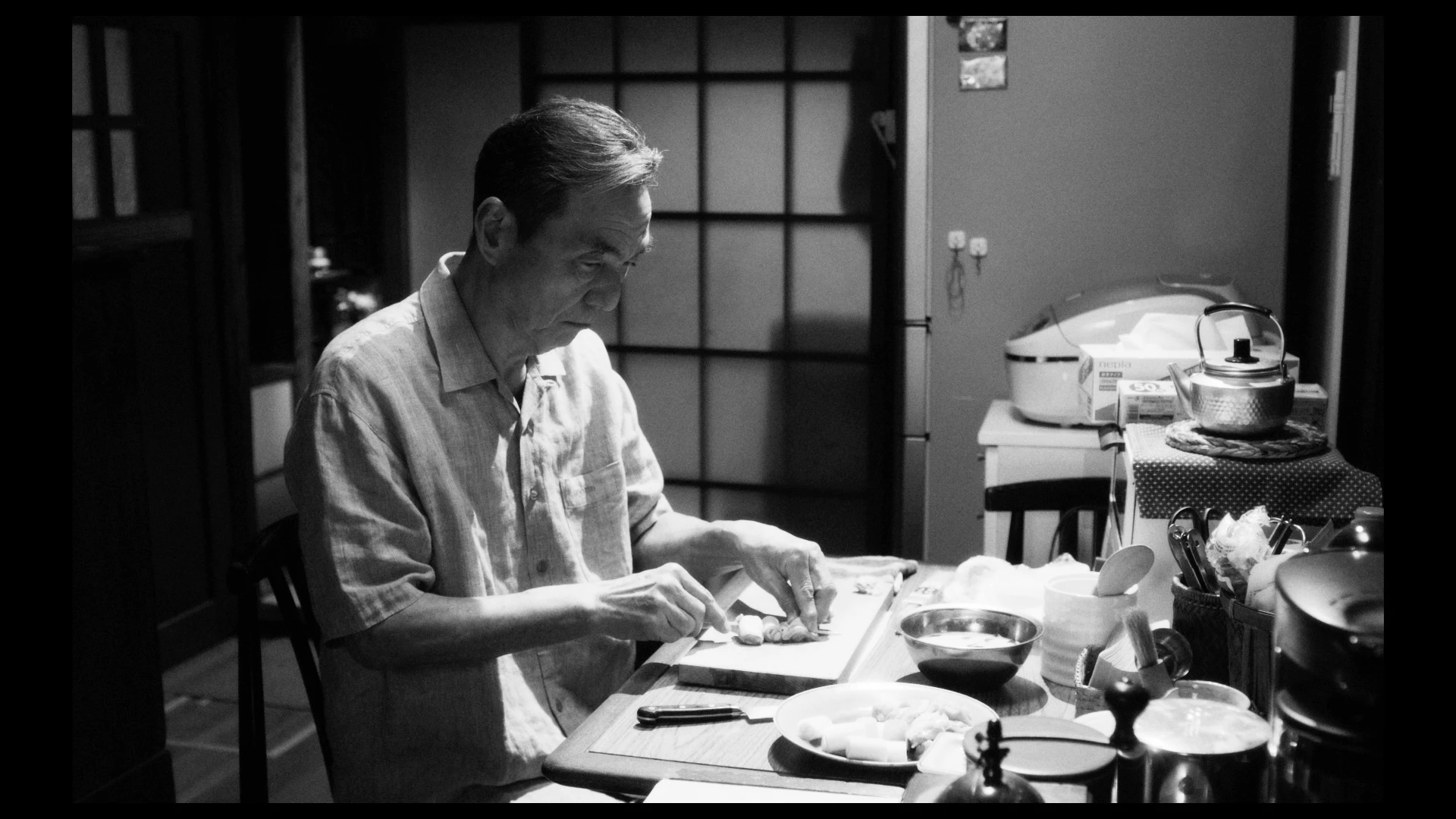

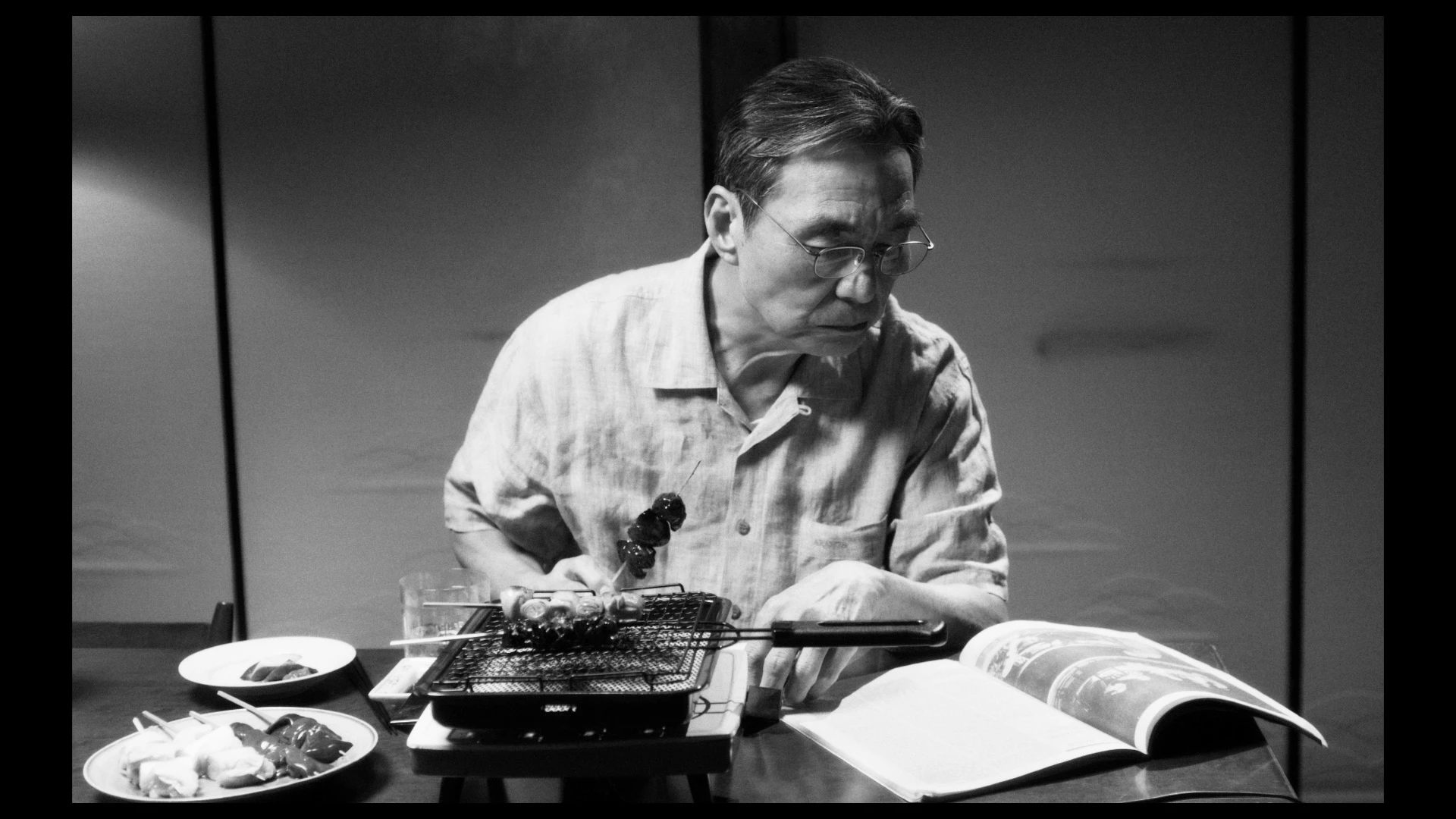

How important do you think the use of black-and-white photography was in terms of creating the atmosphere?

At first, I felt very casual about it, and was influenced by watching black-and-white films before shooting, and intuitively thought that black-and-white would be good for expressing the stoic lifestyle of the protagonist. I found that black-and-white makes it easier to express a fine gradation from light to darkness and without colour, viewers can focus more on the story. It was also a coincidence, but as I started doing it, I found it so enjoyable.

The house you use almost becomes a character itself. How did you find it?

There were parts of the house that were left almost exactly as they were when it was built about 100 years ago. When I found it by chance, I thought it was almost like a miracle, because it was in such a beautiful condition, preserved, and the fact that a couple actually lived there surprised me. I think finding that house was a really big deal, just like in this movie. In Tokyo, when walking around the city, you will see many new buildings, but occasionally a few old buildings are also left standing. But it was extremely difficult to shoot within the house as the space is so small.

Was there a fear that contemporary audiences wouldn’t connect with a black- and-white film?

Many people were initially scared or anxious about what it would be like, but after seeing it, they forgot that they were watching a monochrome film within five minutes. Hearing such stories made me very happy and I think it turned out just as I had hoped.

When watching the movie, I was writing down what I thought the protagonist was feeling, and the words I wrote were regret, fear, doubt and guilt.

That’s right. It’s something that happens if you are a sincere person. That’s right. If everyone is honest with themselves, then they will think deeply about those words. Unless you are someone like Trump.

He is also a man who is so wonderfully set in his ways and his daily routines. Why is that an important part of his character?

Tradition is his support, it’s what he builds his life on. Memories trouble him, so I believe it’s important that his house exudes a sense of tradition, of a place filled with his various memories and experiences. Good and bad – they’re what he can return to and they support him, they comfort him, even when he’s haunted by his memories and his dreams.

We have to talk about the food. Even in monochrome it made me hungry!

Your brain might be seeing black-and-white food, but those images can somehow still convey the smell and taste. As your brain processes those images it still allows you to feel your emotions. The original work is a long novel, but the first half is mostly descriptions of food. Given time, there are recipes to make about 10 times as many different dishes as now remain in the movie. But we spent a lot of time choosing them and if that’s your reaction then we’ve succeeded, because they made us all hungry, too.

Also see: #review: Does Lady Gaga truly bring Mayhem with her new album?